April 15, 2022

A few weeks ago, I bought a Ukrainian Easter egg decorating kit. If you’ve never seen Ukrainian Easter eggs, they are incredible works of art — intricate designs and vibrant colors somehow delicately painted on the fragile shell of an egg. It takes a combination of hot wax, multiple shades of dyes and unending patience to create.

If you’ve ever tried to make your own Ukrainian Easter egg — known as pysanka — you know that it’s probably an endeavor that no novice should attempt. I’ve made them a couple of times in my life, and every time they wind up looking like a 5-year-old’s crayon-drawing version of an Easter egg, complete with shaky, misshapen lines and unintended blobs of color.

Still, I want to try again.

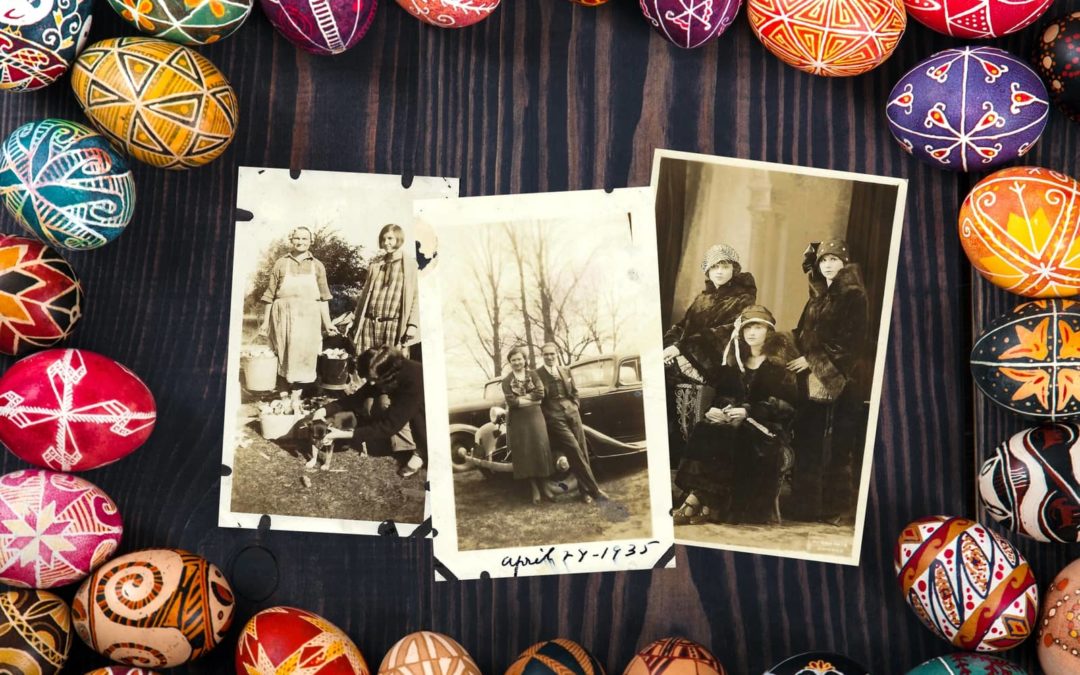

When Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, the tug I’ve always felt toward my Ukrainian heritage grew stronger. I’ve found myself suddenly craving my grandmother’s varenyky, the cheese-filled dumplings that are a variation of Polish pierogies. I’ve had flashbacks to the Easter sausage that my older brother and I used to devour every year when we were children … until one year we helped my grandmother make it and I literally saw how the sausage was made and was turned off for good.

And as this Easter approached, I found myself wanting to recreate parts of the feasts she used to make for us at this time of year. Most notably, I wanted Ukrainian Easter eggs and my grandmother’s paska, a rich, eggy bread flavored with saffron.

Growing up with Ukrainian traditions

My mom had all kinds of stories about growing up as the daughter of Ukrainian immigrants, about learning smatterings of the language and songs, and hearing stories of the country where her parents were from. All of it piqued my interest enough that I minored in Russian literature and took Russian language classes just for fun several years ago.

Our favorite story, though, was of how she’d go to her family’s Russian Orthodox Easter Mass with a basketful of hard-boiled Easter eggs in an attempt to “win” eggs from her fellow churchgoers.

In these “egg battles,” one egg owner would tap another’s oblong point to see which egg escaped uncracked. The egg that cracked would be surrendered to the intact egg’s owner. This would continue throughout Easter morning, and the owner of the strongest egg in the church would go home with a basket filled with (cracked) egg rewards.

My mom taught us a special trick passed down from her own father for learning which egg shell was strongest — by tapping it against your front tooth. The pitch it makes from tap-tap-tapping can tell you how strong the shell is.

Every Easter in my life, we’ve tapped hard-boiled eggs against our front teeth in preparation for our family egg battles.

Until four years ago, that is. Easter Sunday four years ago was the last time I had an egg battle, and it was the last time I saw my mom.

Easter, now complicated by grief

Four years ago, as my mom battled the final stages of uterine cancer, I went back to Michigan to visit family and celebrate the holiday. By Maundy Thursday, my mom was in immense pain and in the emergency room. By Easter Sunday, we were gathered for dinner while my mom was in the hospital. I left her that evening, telling her I was driving home to Charlotte the next day, but would be back soon.

Ten days later, I was at the airport about to fly back to be with her when my brother called to tell me she had died early that morning.

Each Easter since then has been complicated. One year afterward, we awkwardly gathered to celebrate her life, our grief still too raw to really talk much about how deeply we felt her absence. Two years later, it was 2020 and my family was separated by the coronavirus. Last year, freshly vaccinated, we came together in Michigan, but cobbled together an Easter dinner when I realized no one had planned anything. No one made Easter eggs. No one had egg battles.

This year, I can’t help but think about how my Ukrainian mom would view and react to what’s happening in her homeland. In my mind, I always intertwined Russian and Ukrainian cultures because they are so similar and connected. But I see now why my mom always proudly specified she was “100% Ukrainian.”

My grandmother was the first of her family of six children born in the United States; her three older siblings were born in Pavoloch, a small farming town southwest of Kyiv. My grandfather was from a city northwest of Kyiv called Ovruch. I’ve always wanted to visit both places. When I looked at a map of bombings in Ukraine a few weeks ago, a large red triangle signaled a direct hit on Ovruch. I’m not sure if I’ll ever get there, now.

Watching the news every night and seeing the horrific scenes of death and destruction in Ukraine makes me want to support and connect to the Ukrainian side of my family even more.

And until now, I never realized how interwoven with Easter so many of my Ukrainian memories are.

How to make Ukrainian Easter eggs

From my limited experience, making Ukrainian Easter eggs requires having a vision of what you want the final product to look like, and an ability to work backward. Want a red line bisecting a white circle? You have to apply the wax in a circle on the undyed egg first, color the egg in red dye; apply wax in the shape of the red line you envision, and then color the egg a darker color.

The stylus used to apply the wax is a finicky tool called a kistka with a cone-shaped piece of metal attached to a wooden handle with wire. The cone is heated over a candle, used to scoop up dried beeswax from a square block of the stuff, and then heated again to melt and apply to the egg.

When you’re finished creating the pattern you want in wax, the entire dried wax application is melted over a candle flame and wiped away to reveal the colorful design.

Wax is melted off a Ukrainian Easter egg to reveal the colorful pattern. / Getty Images

It’s all very time-consuming and requires a gentle touch. Traditional pysanky are decorated on raw eggs, with a pinprick hole used to drain the egg’s interior. They are meant to be displayed as art, not the kind of eggs you turn into egg salad sandwiches.

Of course, when we’ve made Ukrainian Easter eggs in the past, we’ve used hard-boiled eggs because we are keenly aware of our own clumsiness. Plus, with hard-boiled eggs we can have our egg battles with our finished products.

I have a vision for how I want Easter to be this year, and I’m working backward. I’m planning on making varenyky. I’ve bought saffron for making paska.

And I have a Ukrainian Easter egg decorating kit that I’m bringing back home with me to Michigan. I’ve warned my brother to make sure my niece and two nephews are ready to be creative.

And to prepare for tap-tap-tapping eggs on our front teeth before egg battles.

My mom, I think, would be proud to know that her traditions are living on.

Recent Comments