Slim Bouler carted his scrapbooks to Charles L. Sifford Golf Course in Charlotte, and now he’s flipping through the pages as he sits outside the clubhouse of the 9-hole course where he first learned the game that both earned and cost him so much. He’s pointing to photos of himself with celebrities and athletes, pictures of parties and red carpets from long ago. Nearby, his friends smile and chuckle. They have seen this before.

There’s James (Slim) Bouler at a fancy gathering, posing with Dan Marino. And there he is smiling with Larry Bird, Lawrence Taylor, Mike Tyson.

“Stedman—that’s Oprah’s old man,” Bouler says, showing a visitor a picture of Stedman Graham, Oprah Winfrey’s longtime boyfriend. “I had Stedman out here to the golf course.”

He has page after page of photos of stars slipped in next to laminated articles about the seminal moment of his life. He carries those headlines around, too, when he wants to tell his story, which is often. He pauses his page turning, his baseball cap pushed back from his forehead, his long, spindly legs that earned him his nickname stretched in front of him. He’s 66 years old, 17 years removed from prison, and even as he reads the old newspaper articles, he’s still trying to piece together how he went from a glamorous life to the ordinary one he lives now.

“‘Bouler drug trial today,’” he reads one headline aloud, his distinctive Southern drawl mixed with a muffled throatiness. “They blowed it up: ‘Businessman Bouler indicted on new charges, unrelated to check from Jordan.’ ‘Golf hustling credible claim.’”

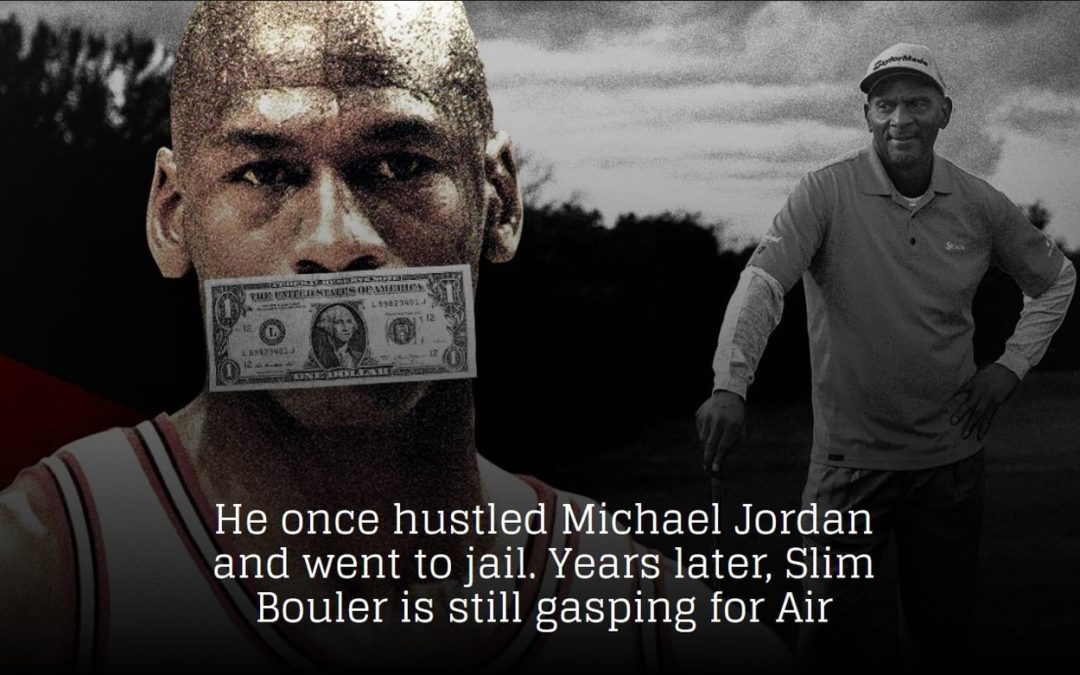

These headlines are from 1991 when Bouler was found to be in possession of a check for $57,000 around the same time $153,000 in cash was discovered in his bags at the Charlotte airport. All of that eventually led to a handful of federal criminal charges—and his life story forever intertwined with Michael Jordan’s.

Twenty-five years ago, a few months after Jordan played for the Dream Team in the 1992 Olympics, he testified for nine minutes in Bouler’s criminal case—because that $57,000 check was from him. It was to pay off a gambling debt from a five-day golfing spree at Hilton Head Island. Jordan was never implicated in any crime, never suggested by federal prosecutors to have done anything more than hang around with an unsavory crowd that included Bouler, who pled guilty to cocaine possession in 1986. That was the same year he met Jordan and began a friendship built on golfing and betting.

Bouler has been out of prison since 2000, lives in the same city where his old golfing buddy now is the owner of the NBA’s Charlotte Hornets, and sometimes he wonders why he’s never heard from Jordan in all those years.

“You’re a billionaire,” Bouler says about Jordan. “I mean, you’re a billionaire and me and you are all right. They (federal investigators) come to me to try to knock you out, I mean, you ain’t got no career if I cooperate with the government. I don’t cooperate. They take everything I got. They take my life for eight years. I can’t go back and get that. When I come home, what you gonna do for me? What would you do for me? You’re a billionaire. What would you do for me?”

Bouler is prone to vague assertions in the colorful stories he tells about his life. He says he won Donald Trump’s golf tournament and visited his penthouse but the details stop there when he is pressed; he claims he was once thrown out of Las Vegas but is evasive about particulars; he repeats over and over that he bet “more than a dollar but less than a million” with Jordan in golf matches over the years.

But he is specific when he says he believes the only reason he was targeted in 1991 for money laundering and drug trafficking charges is because he had a $57,000 check from Jordan.

“They wanted a lie,” Bouler says. “They wanted me to say that it was tied up in drugs.”

And because he didn’t, Bouler wonders why he’s never heard from Jordan.

“If the shoe was on the other foot—you saved my life, my career?” asks Bouler, positing what would happen if the tables were turned and he was the wealthy one and Jordan was an everyday person. “Whatever you want, you got it. I’m a billionaire.

“Put (some money) on the front porch in a bag. Hey, everybody can’t watch you all the time. Put it on the front porch in a bag, I’ll know where it comes from. I wake up in the morning, there it is on the front porch. Hello.”

Bouler hasn’t talked to Michael Jordan since 1991, he says, when they came back from a golfing trip in Hilton Head Island. That was during the same time frame Jordan was supposed to be with his Chicago Bulls teammates at the White House, meeting President George H. W. Bush after his team won its first NBA championship. Instead, as Bouler and Jordan admitted in court later, the two were among a group that spent five days golfing and gambling, and Bouler emerged $57,000 richer. That was just one outing of what Bouler estimates were about 50 with Jordan over a span of 6-to-7 years.

Bouler repeats his signature phrase often: “I went from the outhouse to the penthouse to the jailhouse playing golf.” The Charles L. Sifford Golf Course where he often hangs out now is the same Charlotte course he used to sneak onto because blacks were not officially allowed to golf on it until 1957 and not fully welcomed for a couple decades more.

Bouler lived near the course in a house without running water, taught himself to golf with one club he owned, and he became such a star on the links that by the mid-1980s he had earned enough money from gambling on golf matches to buy his own pro shop and driving range in Monroe, North Carolina, just outside Charlotte.

One day, Jordan showed up at a course down the street from Bouler’s pro shop.

“Hey Slim, Michael Jordan’s down at the course,” someone told him.

“So what?” Bouler responded.

“They’re gambling,” the man said. “For 50, 100, 200, whatever.”

Bouler turned to his club pro on staff.

“Get out our clubs,” he said. “We’re fixin’ to go to work.”

Bouler says he introduced himself to Jordan and asked to get in the game. He quickly won $200. Then he doubled his winnings, then tripled it. “From that day till the day I went to prison, we gambled all the time,” Bouler says.

There would be occasional golf games around the Charlotte area, but more often, big weekends at Jordan’s vacation home in Hilton Head Island. Bouler and the regular crew of 15-20 men settled into a routine: They’d arrive at Jordan’s house at 7 a.m. and eat breakfast (eggs, bacon, ham and coffee) that a housekeeper prepared for them. At 8 a.m., they’d be on the golf course, making wagers.

Bouler and Jordan were part of what Bouler called “The Big Group.” That was the high-stakes bunch that would regularly bet up to $1,000 per hole. Bouler told The Washington Post in 1993 that Jordan could lose up to $20,000 on a bad day.

“If that’s what they say I said, then it’s true,” Bouler says now.

After a long day of golfing, they’d have a lavish, multi-course dinner prepared by housekeepers and then there would be poker. Bouler says he never played cards, but he’d often ask for a slice of Jordan’s winnings after loaning him cash if Jordan was short. Following one such a weekend, Bouler had a cashier’s check from Jordan for $57,000. From that particular binge, Bouler says, Jordan owed more than $100,000 to other acquaintances, too, including Eddie Dow, a Gastonia, North Carolina, gambler and bail bondsman.

At the time Bouler, unknowingly, was under investigation as a suspected cocaine trafficker. His phone was tapped and he was overheard attempting to make plans to avoid paying taxes on that $57,000 check.

Federal authorities seized the check, and Bouler was indicted on drug and money-laundering charges. The government alleged he used his role as a golfer to disguise his real job as a drug courier for two Charlotte cocaine dealers.

But Bouler filed to have the $57,000 returned to him because, he said at first, it was a loan from Jordan to open a driving range. When The Charlotte Observer asked Jordan about the check he said, “It’s totally true. It’s a loan.”

But Bouler soon admitted to authorities that it was his winnings from betting on golf with Jordan, and the NBA superstar changed his story, too. “I was caught off-guard by the question and I was too ashamed of what I had done,” Jordan told the Chicago Sun-Times on Oct. 16, 1992. “But when I realized my mistake and discovered the background of the people I had been with, I told the truth and offered a public apology.”

By then, Jordan—who did not respond to an interview request through his manager for this story—was deeply enmeshed in the story. The NBA began investigating his gambling habits and he prepared to testify in Bouler’s criminal trial.

===

By the time Bouler’s trial began in late 1992, Jordan had won another NBA title with the Bulls and a gold medal with the USA men’s basketball team at the Barcelona Olympics.

“Michael Jordan was at a pinnacle in his athletic career,” Bouler’s lawyer, James Wyatt says now.

Dozens of reporters staked out the entrance to the courthouse the day Jordan was scheduled to testify in Charlotte and went rushing to a limousine that drove up to a side door. It was a decoy. Jordan pulled up to the front door in a nondescript car, hopped out and ducked his 6-foot-6 frame to fit through the metal detectors.

When Jordan took the stand, Wyatt attempted to introduce the famous witness with a bit of levity. “Would it be fair to say you’re the man on the Wheaties box?” he asked.

“Yes,” Jordan answered with an embarrassed smile.

In the courtroom, Bouler listened to his old golfing buddy reaffirm that the $57,000 check was, indeed, from him to pay off gambling debts. Jordan said there was no talk or use of drugs during the Hilton Head trip. He said he golfed with Bouler 8-10 times over the previous four years, betting up to thousands of dollars per game.

Bouler listened while wearing his golfing clothes, his red-and-white golf bag nearby. He dressed as a golfer for each day of the trial to emphasize to the jury what his job was. After a four-day trial and four hours of deliberation, the 12-member jury found Bouler guilty of money laundering but acquitted him of the drug charges.

And that was it, the last time Bouler heard from Jordan, he says.

The government kept Jordan’s $57,000 check, saying the money was compensation for Bouler’s money laundering. In 1997, it was awarded to the Union County (N.C.) sheriff’s office as part of the National Asset Seizure and Forfeiture Program.

Meanwhile, the NBA investigated Jordan’s association with Bouler and the bail bondsman, Dow, who was murdered in February 1992 during an unrelated burglary. Another acquaintance of Jordan’s, Richard Esquinas, wrote a book in which he alleged he had won $1.25 million from Jordan while playing golf. No misconduct was discovered, though then-NBA commissioner David Stern suggested Jordan needed to be more discriminating when choosing associates.

“If you’re in the public eye, you’re going to have to be more careful,” Stern told The Chicago Tribune. “If we have players who it turns out have not been careful, we’ll have to tell them again. It’s a very serious matter.”

A year later, just before the start of the 1993-94 season, Jordan abruptly retired from the NBA—for the first time.

Bouler served eight years in prison in six states for the money laundering conviction. “What they call ‘Diesel Therapy,’” he says. “When you don’t work with the government, you’re going to get some therapy.”

He moved back to Charlotte when he was released in 2000, and he now works as a deliveryman and courier. He golfs as frequently as he can, still often beating his opponents, still often making some extra cash from his skill at the game.

“You’ve got to have money to make money,” he says of the lower stakes he plays for now.

He misses his house that was seized by the government, the one near the home of singer Randy Travis outside Charlotte. He misses his four cars that were confiscated, too. He misses his maid. Maybe most of all? “I miss my 18 beagles,” he says.

His friends have heard all his stories and seen all the photos in his album countless times. They let him do the talking. “That’s his thing,” says Leroy Roseboro, a 71-year-old buddy who’s known Bouler for about 50 years. But Roseboro is quick to add, “He’s got the biggest heart you’ve ever seen. He’s got a heart of gold.”

Bouler still organizes and plays in charity golf tournaments, and he plans an annual charity event to provide food for homeless people in the area. He is an unofficial spokesman for the Charles L. Sifford Golf Course that has a deep history in Charlotte.

“Slim has been one of my favorite clients,” says Wyatt, the lawyer. “We stay in touch regularly and you can’t help but be captivated by him if you sit down and talk with him. He grew up during a racially segregated time, yet as a black man taught himself how to play golf and was able to make a living basically playing stakes golf matches. He’s a fascinating individual.”

He’s rebuilt his life, and he’s slowly coming to terms that he hasn’t heard from Jordan since he has been released. It would be nice if Jordan reached out, but Bouler understands.

“If he has conversations with (people like me), the journalists will probably write, ‘Michael still having contact with convicted felon,’” Bouler says. “When will a man become whole again? You can go through life and still have a brand on your head and you done give society what they want. Do that make sense? When do you become whole again?”

Is Bouler talking about Jordan or himself? Before he can clarify, he grins. “How many black golfers have you seen that took down one of the greatest athletes of all time?” he says.

He’s written a book, he says. He’ll have the full story in there. Someday, when he has enough money to get everything together, he’ll have it published.

He already has the title: “I Bet on Air and Lost it All.”

Recent Comments