July 7, 2023

When Amanda Dumas heard details about the latest North Carolina bills aimed at limiting medical treatment of transgender children, the door to the place where she holds back her rage cracked open again.

Just as she was about to head to her youngest child’s monthly counseling session, she saw that a bill banning puberty-blocking drugs and hormone therapy for transgender minors was revived by the state General Assembly.

And she figured before 12-year-old Michael talked to his therapist, she might as well tell him that the puberty-blocking shot he receives every three months might soon be barred by North Carolina.

The shots prevent Mike from going through puberty, stopping him from developing breasts or starting to menstruate. The shots allow Mike to continue to live as the boy he’s been since he was 5 years old.

Amanda and her husband, Josh, have seen the wave of laws barring gender-affirming treatment of transgender children enacted across the country this year, swelling like the tide and inching toward them. It’s at their toes now, and they can’t ignore it.

For years, Mike and his family have been helped by therapists and doctors who’ve consulted with volumes of research on the best approaches to raising a transgender child. They’ve put a plan in place to advance from Mike’s current puberty blockers to hormone therapy that will allow his body to transition physically to the gender he’s always identified as.

But now, that plan is at risk of being upended by politicians, not experts in human physiology or psychology. And Amanda and Josh are both furious and desperate.

“The doctors, the scientists, the researchers — they’ve got it,” Josh said, pointing his hand at an imaginary handbook of guidelines, as if it were sitting beside him in his Huntersville kitchen. “This is what you do.

“And you have politicians who don’t know what the hell they’re talking about saying, ‘I know better.’ And you have people in the world who don’t know what the hell they’re talking about saying, ‘Well, I don’t want that for me, so you can’t do it either.’ And that’s probably the most frustrating part.

“And that’s my kid. That’s our family. We’re not a political football, but that’s how it’s being treated.”

“For some reason this has become a lightning-rod issue. And that’s the scariest part — that it’s so bereft of logic. It’s all emotion, it’s all fueled by hatred. And someone out there sees an opportunity to isolate this community and attack them and gain something from it.

Stay and fight

A couple months ago, Amanda and Josh sat down with Mike and their 15-year-old son, T.J., for a family meeting. At the time, there were two main North Carolina bills under consideration that would limit or prevent gender-affirming care for transgender children, along with a bill prohibiting transgender girls and women from participating in high school and college sports. All of it feels like a personal attack.

The Dumas family talked about what it would mean to minimize their lives, to deactivate their social media accounts and pull back from social engagements so that they don’t feel scrutinized and Mike could continue his treatments.

Or they could move, Amanda and Josh suggested. Maybe to somewhere in the Northeast, where there are friendlier laws and more liberal state governments. Maybe to Canada, where Amanda has dual citizenship. Maybe even to Europe if they have to.

Or, they could stay where Mike has lived for nearly his entire life, where he’s found friends and become a happy and goofy kid in the community they’ve built in 11 years in North Carolina.

“Do we want to fight and try to save our home and be able to stay here and for everybody to be safe and make a difference in this community?” Amanda asked.

“We decided we would stay and fight,” she said.

This is not a fad

Here is what Amanda and Josh Dumas would like you to know about parenting a transgender child:

No, this is not a fad.

Yes, they know he’s young to understand something so big about himself.

No, this is not “just a phase,” either.

“This notion that the opposition has, that we’re forcing this on our kids or kid — or that anyone is — is insane because that’s not what happened,” Josh said. “It’s the complete opposite. I guarantee you, the kid is leading the charge and the parents aren’t prepared.

“Parents are going to do whatever they can to try to figure out how to keep their kid in the guardrails. And it’s only when they listen to their child and are able to accept that this is probably a reality and start to explore it do you kind of figure out who they really are. No one’s asking for this.”

Thinking back now, there were hints from the earliest years that their kid, who they refer to as “they” when describing his earliest years, was unhappy and uncomfortable.

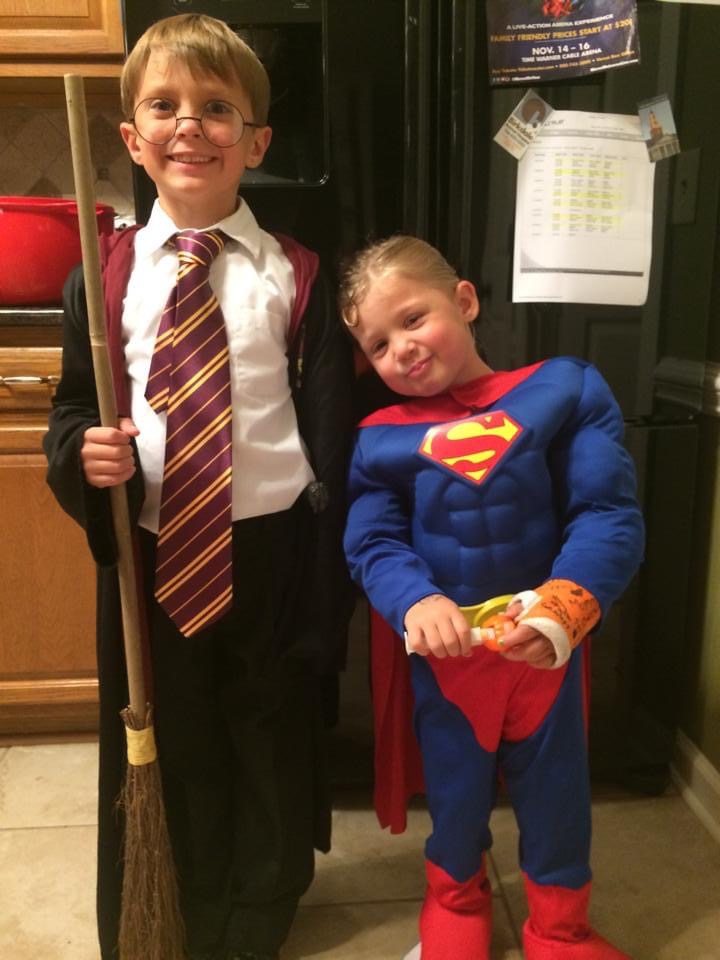

As a child, Mike always wanted to be a superhero for Halloween — and always Superman, never Supergirl. They loved to tag along with their older brother, engaging in sports and playing with action figures. There was absolutely no interest in traditional girl toys or activities. The one year they tried dance lessons, they simply stood in protest during the recital because the simple red dress was so uncomfortable.

But there were larger behavior issues that signaled something deeper, too. Screaming fits until they turned beet-red. Hyperventilating. Lashing out by throwing things, all while being inconsolable. Amanda and Josh tried to sit patiently with them, removed things from their room, even locked the bedroom door from the outside. Amanda thought that if she could just hug their child tight enough, hold them and comfort them, that it would somehow help.

“But if you touched them, they were even worse,” Amanda said. “They would destroy everything in their room. They clearly hated something and we couldn’t figure it out.

“We were just destroyed every night, exhausted trying to parent this child who was miserable.”

Mike barely remembers any of it. He recalls throwing things a few times, thinking, “I really want to throw this.” He remembers being upset and crying often.

Still, Amanda and Josh tried to ignore it. When their child, at age 4, began begging for their shoulder-length hair to be chopped off into a “Joey Tribbiani” look, like the “Friends” character, they laughed it off. But Amanda also started searching online message boards for the terms “child” and “gender identity.” She pulled her pediatrician aside and asked what to do.

“Just don’t give them the haircut,” the doctor advised.

But for their child’s fifth birthday, they finally relented. “I think deep inside we both knew that by cutting his hair, it was opening a door. And that’s why I think we pushed away from it for a year,” Amanda said.

“Can you just give them a nice pixie cut?” Amanda asked her hairstylist.

With a short, stylish haircut, a stranger in Lowe’s called the kid, “Buddy.” Mike beamed.

“That was the first time we saw him glow,” Amanda said.

About two weeks later, they finally caved to a full buzz cut.

This has never been easy

Amanda Dumas was slowly starting to realize that something was happening with their youngest child’s gender identity, and started seeking people and groups who could give her advice.

She talked to psychologists and doctors who counseled that if the behavior was “consistent, persistent and insistent,” then they should support their child’s chosen gender.

She found PFLAG, an organization that is “dedicated to supporting, educating, and advocating for LGBTQ+ people and those who love them” and connected with parents who had similar stories. Still, it’s rare for children younger than 13 to identify as transgender, and no federal data estimates how many do in the United States.

One of the experts suggested allowing their kid to use a chosen nickname.

“What do you think of Michael?” her child asked Amanda one evening.

“It’s a nice name,” she said. “It’s my ex-boyfriend’s name.”

“Can that be my nickname?” he asked.

“Yeah, we can try that out,” Amanda said.

He raised his arms high overhead and roared, “My name is MICHAEL!”

“And he was just so confident,” Amanda remembered.

But at first, Josh struggled with all of it. It had been a matter of months between the haircut and their child selecting the nickname Michael and he wasn’t sure if any of it was right.

“There was a combination of Mike being so young, of it being super, super scary,” he said. “Like, that was something you could never go back from. That’s what it felt like.”

And there was the notion that what they’d both believed to be their perfect little family — two loving parents, a son and a daughter living in the Charlotte suburbs — was about to disintegrate.

“We mourned the idea of the child we thought we had,” Amanda said, “the expectation of who they were supposed to be.”

Amanda had long dreamed of the bond she’d have with her daughter, of how she’d pass along her former beauty pageant dresses and maybe share a joy for figure skating and dancing. She’d given her daughter her grandmother’s name, the one she’d wanted to bless her child with since Amanda was young. So, one day not long after Mike chose his new name, Amanda was sitting in her driveway after another therapist appointment and her neighbor, Jamie Rule, asked how she was doing.

“And she just kind of broke down,” Rule said. “It was just a huge thing for them to think for so long that they had a daughter and then kind of trying to figure out how you change that. It’s something completely different than what you expected.”

Rule grew up in a conservative, religious family, and had never encountered anyone who was transgender. But she gave Amanda the advice that she would want to hear if she were in the same position.

“You want what’s best for your kids, and you want them to be happy,” she said. “So what’s it going to hurt to let him be who he wants to be?”

That was also the year when Amanda and Josh felt cracks forming in their marriage, even if just the tiniest bit. “But it wasn’t long,” Josh said. “We did the right things and we got on the same page.”

“Of our 24 years together, that was the hardest,” Amanda said.

T.J., who was 8 at the time, said the biggest adjustment was in suddenly calling his sibling a different name. But his immediate reaction is one the family still laughs about today:

“Cool, I always wanted a brother,” he said enthusiastically.

Doing whatever it takes

Here is something else Amanda and Josh want you to know about having a transgender child:

Since Mike began living as his authentic self, the panic attacks and destructive behavior have vanished. He’s comfortable in his own skin. He smiles more. Yes, there are arguments with his parents and fights with his older brother. But it’s all the relatively normal stuff of an average 12-year-old.

“And it kind of feels like, and they never looked back,” Josh said. “There’s still issues, but it really feels like the last seven years, it hasn’t been that big of a thing. I’ve had more sleepless nights and stress over my older son’s issues with getting his homework done.”

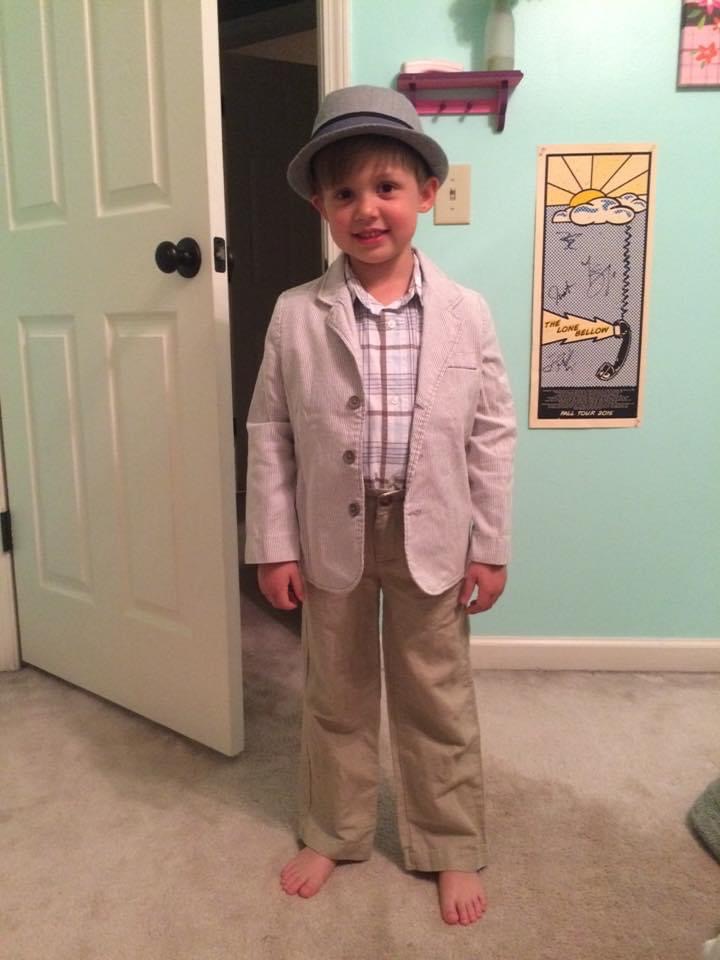

Mike has shaggy, sandy-blond hair, the straight-line body of a child, boundless energy and a teenager’s dry wit. He’s on the neighborhood boys swim team and his parents gush about his butterfly stroke. He loves playing and watching hockey. He’s fascinated by weather patterns and aspires to be a meteorologist. He’s the head of an unofficial pickle club at his school, but doesn’t even like pickles.

He recently had a girlfriend for a few months who didn’t know the gender that’s still on his birth certificate. When some kids at school told her, she was mad for a few days, but then the two resumed dating — as much as 12-year-olds date. They’re still friends.

“We’ve watched Mike grow up and he is so happy being able to be himself,” said Rule, their neighbor. “We don’t even think about what was. It feels like he’s always been Mike.”

The puberty-blocker shot that Mike receives every 11 weeks prevents estrogen from being produced by the ovaries. That halts breast tissue from developing, stops eggs from maturing and inhibits menstruation from beginning. But it also delays a looming decision: whether to begin hormone therapy treatment. For now, the blockers are buying them time to get accustomed to everything and make sure this is the best course of treatment.

“It’s a really good thing to be able to kind of hit the pause button and say, ‘You know what? Let’s give this a few years. Let’s give everybody a year or two for him to grow, for us to learn more, for us to think about it more, and we can kind of wait on puberty,’” Josh said. “Because once puberty hits, so many things happen that are irreversible.”

Doctors caution that long-term studies are limited, but thus far they’ve found no enduring side-effects from puberty blockers. Even so, Mike has regular bone-density scans and bloodwork so doctors can monitor his health. When he first started getting the blockers at age 9, Mike admitted he was scared.

“Scared of what?” someone asked.

“Scared it wouldn’t work,” he said quietly.

If Mike begins taking weekly shots of testosterone there will be permanent changes. His vocal cords will thicken and his voice will deepen. He will begin growing facial hair. He might start losing hair on his head. He risks losing the ability to have children.

“It’s not an overnight decision,” Amanda said. “It’s so many doctor visits and it’s so many conversations; so many tears. But it’s what he needs. He is desperate to start testosterone. If it were up to him, he would be taking it now.”

It’s also not cheap. Insurance declined to cover Mike’s puberty blockers at first, and Amanda and Josh were poised to dip into their retirement savings to foot their $50,000 annual out-of-pocket bill if they had to.

“You think I want to be spending my money on a shot in his butt to make sure he doesn’t develop?” Amanda said. “I’m not forcing this on my kid. I don’t want to be doing that. But I absolutely, 100% will, and I’ll make sure, no matter what laws are in place, that he will get that health care. Put me in jail. I’ll be your martyr, I don’t care.”

It’s not enough

Amanda and Josh try to limit asking for friends and family to become activists alongside them. Instead, they attempt to educate everyone around them about what it’s like to have a transgender child, and what it’s like for someone so young to realize something so big about themselves. They hope simple information will organically inspire those around them to support transgender rights.

But in the last two years, 20 states have passed legislation restricting or banning gender-affirming care for transgender minors, including 17 in the past year.

At one point this year, seven North Carolina bills aimed at transgender youth were under consideration. When Amanda and Josh heard about House Bill 808 and Senate Bill 631 in late June, bills that would limit gender-affirming medical treatment until someone is 18, they asked for help. They urged everyone they know to contact their state representatives. They shared with them how dangerous the restrictions on puberty blockers and hormone treatment would be for Mike.

Neighbors like Ron and Jamie Rule pledged to help and support. They listen to Amanda and Josh when they need to vent, and Jamie Rule said living next to the Dumas family has changed her life — and her politics. She grew up in a conservative household, but no longer considers her politics to lean that way.

“It’s been eye-opening and made me question certain things that I believed as a kid and teenager because of what was taught,” she said.

Amanda and Josh follow every iteration of the bills, every twist and turn of the legislation, and it swings them from panic to quiet apprehension. In one draft, H.B. 808 contained a line that said any minor already undergoing hormone therapy by Oct. 1 could continue treatment, and they wondered if they should speed up their plan for Mike to begin taking testosterone to make sure he was protected by that clause.

“That is not OK that legislation is impacting the timeline of the health care of our child,” Amanda said.

Lawmakers say the bills are protecting minors from making irreversible decisions about their bodies. They point to a 2022 study that says the number of minors age 13-17 identifying as transgender has doubled in the last five years, and they are concerned about an epidemic of “wokeism.” They fear that when a child is older, they will regret decisions they made. Another 2022 study found that 98% of transgender youth who transition continue their gender-affirming care five years after initial social transition. It’s the 2% who don’t that lawmakers are worried about.

The final version of H.B. 808 that Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed July 5 contains an exception that says any minor receiving treatment before Aug. 1 can continue receiving care. Amanda and Josh interpret that to encompass Mike’s treatment plan that includes advancing to hormone therapy in the next year.

But they worry about another line in the bill that says doctors can be sued up to 25 years after administering hormone or surgical treatment to a minor. It might lead to doctors declining to offer gender-affirming care for fear of litigation, they say.

So they’ve continued to be outspoken in their opposition to the legislation. Republicans in the General Assembly have a supermajority and are expected to override Cooper’s veto. On June 24, Josh stood before a microphone in a public comment session for H.B. 808, his second trip to Raleigh this year to speak to lawmakers.

“I planned today to tell you the whole story of how we transitioned and how we figured things out and how hard it was,” Josh told the Senate Rules Committee. “But the folks who already spoke have done a great job and I’m not going to do that today. Because I don’t think you care. I don’t think you care about me and my family, I really don’t. I don’t think you care about the thousands of trans kids and families in this state that you’re attacking. … At the end of the day, I think the only thing you care about is getting reelected. For whatever the reason, this bill seems to be your path.”

Sitting back at his Huntersville home days later, Josh worried that even if they win this battle, the larger war is still raging. He doesn’t know what other bills might be introduced at the state or federal level next.

“There’s a battle happening over this issue and it’s terrifying to be caught in the middle of it,” Josh said. “We’re doing the best we can, but gosh, we just know that it’s not enough.”

Here is what you should know

Here is what Mike wants you to know about what it’s like to be a transgender kid:

He knows more about politics than any other 12-year-old he knows, even if much of it seeps in through osmosis and listening to the adult conversations around him.

He knows that whatever laws might be passed, his parents will find a way to get him the gender-affirming care he needs. He’s even a little excited about the possibility of more plane flights to get that treatment if he has to.

And he thinks he knows why so many politicians have made laws in recent months banning gender-affirming care.

“Because it doesn’t affect them,” Mike said.

But it affects him and his family in every way.

Recent Comments