June 4, 2019

CHARLOTTE — For nearly three years, Jill Dinwiddie worked quietly. She talked to potential donors about how desperately Planned Parenthood needed a new health center, one large enough to add abortion to the clinic’s services for the first time in three decades. She needed to raise $10 million, find a building in the city’s competitive real estate market and renovate it — all without media outlets or protesters finding out.

Dinwiddie and her co-chairs of the capital campaign committee, Crandall Bowles and Linda Hudson, conducted an under-the-

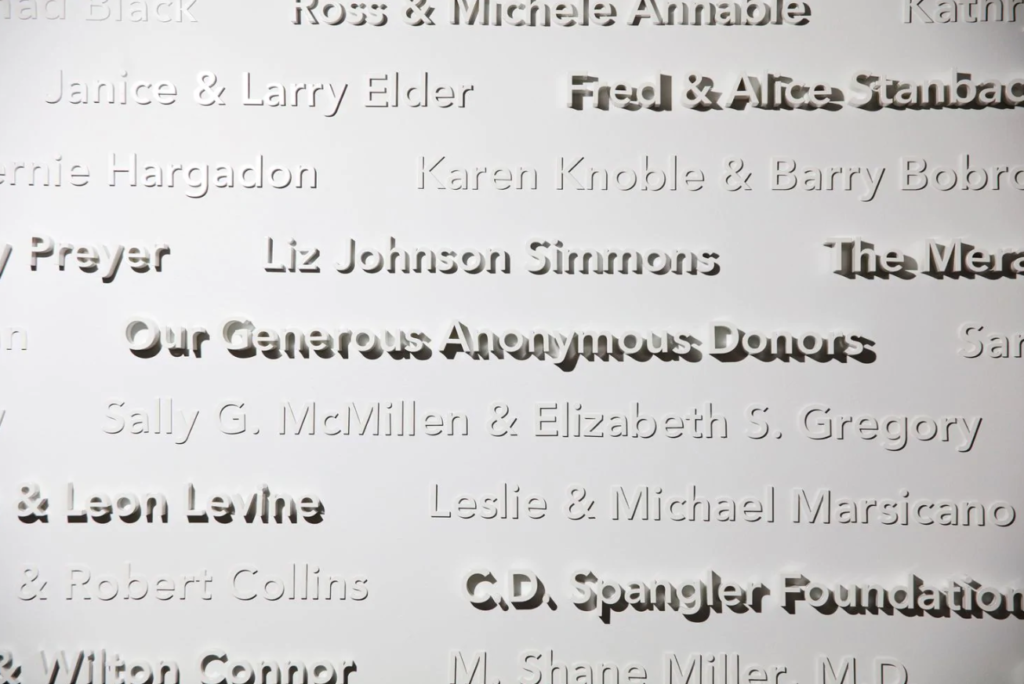

radar search for a real estate agent, purchased a building with a limited-liability company set up to mask the buyer and built a password-protected donation website. When word began to leak to the public about a month ago, the committee already had raised $8.5 million — and a nearly complete health center, more than double the size of the previous facility, stood at 700 S. Torrence St. A ribbon-cutting took place Tuesday, with the operational clinic to open in July.

Even as abortion laws are being rewritten across the country — with several states passing “heartbeat” laws prohibiting abortion after six weeks, Alabama enacting a near-total ban on the procedure, Missouri’s only clinic in jeopardy and Texas seeking to ban cities from partnering with Planned Parenthood — access to abortion is also expanding across parts of the South.

Charlotte is the third Planned Parenthood South Atlantic clinic to add abortion services in the past four years, following Charleston, S.C., last year and Asheville, N.C., in 2015. Ten of the 14 centers in the region will now provide abortion.

The new Charlotte clinic will open as North Carolina’s legislature considers adding further restrictions on the procedure and states gear up for what seems destined to be a challenge to Roe v. Wade.

“We’ve seen this coming for years,” Planned Parenthood South Atlantic chief executive Jenny Black said of newly enacted restrictions. “And we really wanted to put our stake in the ground in Charlotte, and say that access to these services is very important to us and we are going to do what it takes to bring it to fruition for Charlotte.”

Abortion has not been provided at Charlotte’s Planned Parenthood facility since sometime in the late 1980s or early 1990s, when the center moved to its current rented offices off Albemarle Road, about five miles from the city’s center. Three other clinics in Charlotte currently perform abortions, and Mecklenburg County, where the city is seated, is the site of about 36 percent of North Carolina’s total abortions, by far the most in the state. About 39 percent of abortions performed in the county are to out-of-state residents, according to 2017 data from the North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics.

Given those numbers and Planned Parenthood’s cramped, hard-to-find Charlotte office, Black and her team began gathering data and forming a plan for a new facility soon after she assumed her position in 2015. By 2016, Dinwiddie, Bowles and Hudson were working with a committee of supporters to target donors.

After securing their first major gift — $2 million from the Gambrell Foundation — the search was on for a new building location, one that would be near the city, close to hospitals and major freeways, and accessible by public transit. Planned Parenthood called three or four real estate agents before hearing back from one.

“They don’t always return your call when you’re Planned Parenthood,” said Marcie Shealy, Planned Parenthood South Atlantic’s director of philanthropy. “You learn. I’m thinking, ‘Well, they want business.’ Well, they don’t necessarily want our business because people see it as political — although it is not political.”

By mid-2017, they had found a building on South Torrence Street, former doctors’ offices already zoned for medical use, situated midway between Charlotte’s two largest hospitals. Under the name Secure Source LLC, Planned Parenthood bought it for $2.35 million, according to city records.

The organization had learned from recent renovations of its Charleston and Columbia, S.C., facilities how construction could be delayed by too much publicity. After the recession put plans for renovations in Asheville on hold, a fundraising campaign resumed in 2012, only to face delays as protesters disrupted construction. The facility opened in 2015, eight years after the project first was proposed.

In Charlotte, abortion provider A Preferred Women’s Health Center, in particular, has long been the target of numerous and vocal antiabortion protesters. The city council is set to vote this month on a noise ordinance that, among other things, prohibits amplified sound near medical facilities, which protesters have said is aimed at quieting them.

“We really recognized early on that the community of Charlotte is home to some of the most virulent antiabortion activists in the country, and the potential for the project to be slowed down was high,” Black said. “And that we needed to do everything we could to deliver on our promise to the community in a timely fashion. So we did feel like we needed to run the project as quietly as possible — and boy, these ladies delivered.”

Larken Egleston, the city council member whose district encompasses the Cherry neighborhood where the new clinic is located, said the council did not learn of the new health center until recently because new building zoning was not required. Since then, he has heard from those in favor and those against the clinic, and said the city council will keep an eye on protests and traffic near the facility after it officially opens. There have been a few small gatherings of protesters since news of the clinic became public.

But in general, Egleston said, the facility, which includes a call center that will employ about 15 new workers, is welcome.

“I think it’s a positive anytime we can add safe, reliable medical care that people can access,” Egleston said. “I think giving them access to a broad array of medical services in a facility — one of which happens to be controversial but the other hundred of which aren’t — is a good thing for that community and a good thing for the city.” (Abortion accounted for 3.4 percent of Planned Parenthood’s services in 2017, according to its most recent annual report.)

North Carolina’s attempts to restrict abortion have been mixed recently. On May 24, a federal judge struck down a 2015 state law that restricted abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy. The state legislature is now attempting to override a veto by Gov. Roy Cooper (D) of Senate Bill 359, which would punish physicians and nurses who don’t provide care to newborns who survive an abortion. Republicans don’t have a large enough majority in the House to override the veto without some Democratic support.

“This has suddenly gotten to be an even much larger movement than it has always been,” said Bowles, one of the Charlotte capital campaign co-chairs. “I think, actually, it could have been a lot worse for us doing this, in terms of getting attention and getting protests and that sort of thing.”

Added Dinwiddie: “Our timing was right.”

Recent Comments